Introduction: The Brain Under the Grip of Anxiety

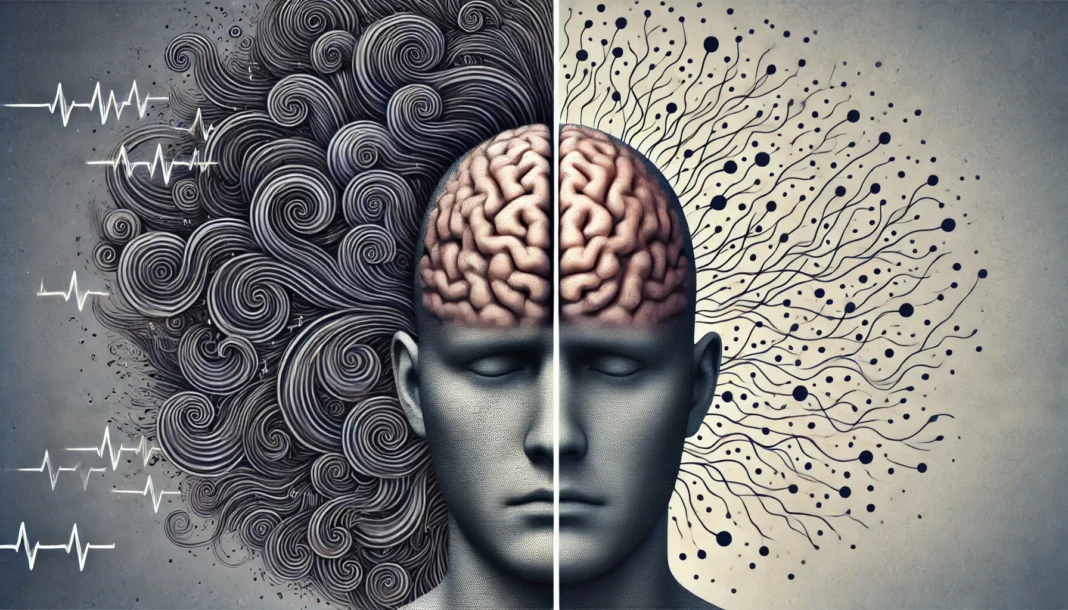

Anxiety is a universal human experience, a biological response to stress that serves an essential evolutionary purpose. However, for individuals suffering from chronic anxiety disorders, the brain undergoes profound and lasting changes that distinguish an “anxiety brain” from a “normal brain.” Understanding the differences between an anxiety brain vs. a normal brain is crucial for recognizing the physiological underpinnings of anxiety and its impact on cognition, emotions, and overall well-being. While everyone experiences occasional stress, chronic anxiety can alter brain structure, function, and neurochemical balance, making it more than just an emotional state—it becomes a neurological condition. This article delves into what causes anxiety in the brain, exploring how anxiety rewires neural pathways, influences neurotransmitter levels, and contributes to an overactive fear response. By examining anxiety and the brain in depth, we can better understand its long-term effects and identify potential avenues for intervention and treatment.

You may also like: Why Is Mental Health Important? Understanding Its Impact on Well-Being and Daily Life

The Neurological Basis of Anxiety: What Causes Anxiety in the Brain?

At its core, anxiety is a complex interaction of neurological processes involving multiple brain regions and neurotransmitters. The amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus play central roles in regulating fear and stress responses. In individuals with an anxiety disorder, these regions exhibit hyperactivity, dysfunction, or structural alterations that amplify fear responses and impair rational decision-making. The amygdala, often referred to as the brain’s “fear center,” detects threats and activates the body’s fight-or-flight response. In an anxiety brain, the amygdala is overactive, sending exaggerated distress signals even in non-threatening situations. This heightened state of alertness contributes to chronic worry, panic, and emotional dysregulation. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for logical reasoning and impulse control, is often underactive in anxious individuals, leading to difficulty overriding irrational fears. Additionally, the hippocampus, which processes memory and context, may shrink in those with prolonged anxiety, reducing the brain’s ability to differentiate between real and perceived threats. These structural and functional differences explain why individuals with chronic anxiety experience excessive worry, intrusive thoughts, and heightened emotional responses.

Neurotransmitters and Anxiety: Chemical Imbalances in the Brain

Neurotransmitters—chemical messengers that facilitate communication between neurons—are critical in the development and persistence of anxiety. The most significant neurotransmitters involved in anxiety and the brain are gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. GABA, the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, plays a vital role in calming neural activity. An imbalance in GABA levels can lead to hyperactivity in the fear circuits, resulting in excessive worry and panic. Serotonin, often dubbed the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, helps regulate mood and emotional stability. Low serotonin levels are strongly linked to anxiety disorders, contributing to feelings of unease, irritability, and obsessive thought patterns. Dopamine, which influences motivation and reward processing, is often disrupted in anxious individuals, leading to an overemphasis on negative stimuli and a diminished ability to experience pleasure. Norepinephrine, responsible for the fight-or-flight response, is elevated in people with chronic anxiety, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and hypervigilance. The dysregulation of these neurotransmitters creates a vicious cycle, reinforcing anxious behaviors and making it difficult for individuals to break free from persistent worry.

Structural Differences Between an Anxiety Brain vs. a Normal Brain

Chronic anxiety not only alters brain chemistry but also induces structural changes over time. Neuroimaging studies reveal significant differences between an anxiety brain vs. a normal brain, particularly in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. The amygdala is consistently larger and more active in individuals with anxiety disorders, leading to exaggerated fear responses. Conversely, the prefrontal cortex often exhibits reduced volume and connectivity, impairing rational thinking and emotional regulation. The hippocampus, crucial for contextualizing fear responses, is frequently smaller in people with chronic anxiety, making it harder to distinguish between actual threats and false alarms. These structural differences indicate that anxiety is not just a transient emotional state but a condition that physically reshapes the brain, reinforcing maladaptive thought patterns and stress responses. Understanding these changes highlights the importance of early intervention and targeted treatments that can help reverse or mitigate these effects.

The Role of Chronic Stress in Anxiety and the Brain

Stress is a major contributor to the development and persistence of anxiety disorders. When exposed to chronic stress, the brain releases excessive amounts of cortisol, the primary stress hormone. While cortisol is essential for short-term survival, prolonged exposure can damage brain structures involved in emotional regulation and memory. The hippocampus, which contains numerous cortisol receptors, is particularly vulnerable to stress-induced shrinkage. Reduced hippocampal volume impairs the brain’s ability to contextualize fear responses, leading to an exaggerated sense of danger. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for impulse control and decision-making, also suffers under chronic stress, resulting in impaired rational thinking and increased susceptibility to anxiety. Meanwhile, the amygdala becomes hyperactive, further amplifying fear responses. This cascade of neurological changes explains why individuals exposed to prolonged stress—such as trauma, chronic illness, or ongoing financial difficulties—are at higher risk for developing anxiety disorders. Managing stress through mindfulness, therapy, and lifestyle changes is essential in preventing these long-term effects on brain function.

How Anxiety Alters Cognitive Function and Decision-Making

Anxiety significantly impacts cognitive function, particularly in areas related to attention, memory, and decision-making. Individuals with anxiety often experience difficulty concentrating, as their brain remains preoccupied with intrusive thoughts and worst-case scenarios. This phenomenon, known as attentional bias, causes anxious individuals to focus disproportionately on potential threats, impairing their ability to process neutral or positive information. Memory function is also affected, as chronic stress and excessive cortisol weaken the hippocampus, making it harder to recall details accurately. Decision-making becomes impaired due to an overactive amygdala and underactive prefrontal cortex, leading to risk aversion, indecisiveness, and heightened emotional reactivity. Understanding these cognitive impairments underscores the importance of targeted interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which helps rewire maladaptive thought patterns and improve rational decision-making.

The Reversibility of Anxiety-Induced Brain Changes

One of the most promising aspects of anxiety research is the discovery that anxiety-induced brain changes are not necessarily permanent. Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganize and adapt, allows individuals to reshape their neural pathways through targeted therapies and lifestyle modifications. Regular exercise has been shown to reduce amygdala hyperactivity while enhancing prefrontal cortex function. Meditation and mindfulness practices help strengthen the connection between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, allowing individuals to regulate their emotional responses more effectively. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is particularly effective in retraining the brain to respond differently to stressors, reducing excessive fear responses over time. Pharmacological interventions, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), can help restore neurotransmitter balance, alleviating symptoms and promoting neural recovery. These findings offer hope that, with the right interventions, individuals with anxiety disorders can restore brain function and improve their quality of life.

Frequently Asked Questions: Anxiety and the Brain

1. How does chronic anxiety change the brain over time?

Chronic anxiety can lead to lasting changes in brain structure and function. Over time, an overactive amygdala—responsible for processing fear—can grow larger and become hypersensitive to perceived threats, making even minor stressors feel overwhelming. Simultaneously, the prefrontal cortex, which regulates rational decision-making, may shrink, impairing the brain’s ability to override excessive fear responses. The hippocampus, a critical region for memory and context processing, is also affected, often becoming smaller due to prolonged exposure to stress hormones like cortisol. These structural alterations reinforce anxious thought patterns, making it harder for individuals to manage anxiety and distinguish between real and imagined dangers.

2. What causes anxiety in the brain, and why do some people experience it more intensely than others?

The root of anxiety lies in the brain’s complex interplay of neurotransmitters, brain regions, and external stressors. Individuals with heightened anxiety often have an overactive amygdala that responds disproportionately to stress. Neurotransmitter imbalances—such as reduced levels of serotonin and GABA, which help regulate mood and calm the nervous system—can also contribute to heightened anxiety responses. Genetic predisposition plays a role as well, with some individuals inheriting a heightened sensitivity to stress. Environmental factors, such as chronic stress, trauma, or early life adversity, can further condition the brain to remain in a heightened state of alertness. This combination of neurological, genetic, and environmental factors explains why anxiety levels vary among individuals.

3. How does an anxiety brain vs. normal brain differ in processing fear?

Anxiety and the brain share a deeply interconnected relationship, particularly in the way fear is processed. In a normal brain, the amygdala reacts to threats, but the prefrontal cortex can regulate this response and help interpret whether a situation is truly dangerous. In an anxiety brain, the amygdala remains in a state of overactivity, frequently misidentifying neutral or mildly stressful situations as threats. This leads to excessive worry and hypervigilance, as the brain remains trapped in a cycle of heightened fear. Additionally, a weakened prefrontal cortex struggles to calm the overactive amygdala, allowing irrational fears to dominate decision-making and emotional responses.

4. Can neuroplasticity help reverse the effects of anxiety on the brain?

Yes, neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire and adapt—offers hope for individuals struggling with chronic anxiety. With targeted interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness practices, and regular physical exercise, the brain can develop new neural pathways that reduce the dominance of fear-driven responses. Over time, these practices can strengthen the prefrontal cortex, helping to regulate an overactive amygdala. Additionally, activities that promote relaxation, such as deep breathing and meditation, can reduce excessive cortisol production and support hippocampal function. By consistently engaging in these interventions, individuals can retrain their brains to respond more calmly to stressors.

5. How do medications affect anxiety and the brain?

Pharmaceutical treatments for anxiety, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and benzodiazepines, work by altering neurotransmitter activity. SSRIs increase serotonin levels, improving mood regulation and reducing excessive worry. Benzodiazepines enhance GABA activity, providing immediate calming effects, though they are typically recommended for short-term use due to their potential for dependence. Other medications, such as beta-blockers, can help manage physical symptoms of anxiety by reducing adrenaline’s impact on the nervous system. While medications can be effective, they are most beneficial when combined with therapy and lifestyle changes that address the root neurological causes of anxiety.

6. Can diet and nutrition influence anxiety levels?

Yes, diet plays a significant role in regulating anxiety and the brain. Nutrients such as magnesium, omega-3 fatty acids, and B vitamins support neurotransmitter function and reduce stress-related inflammation. Foods rich in tryptophan, such as turkey and nuts, help the body produce serotonin, promoting a sense of calm. Conversely, excessive caffeine and processed sugars can exacerbate anxiety by overstimulating the nervous system and causing blood sugar fluctuations. Maintaining a balanced diet with whole foods, healthy fats, and adequate hydration can support brain function and reduce the intensity of anxiety symptoms.

7. How does sleep affect anxiety and the brain?

Sleep is essential for brain function, particularly in regulating mood and stress responses. Inadequate sleep impairs the brain’s ability to process emotions, making anxiety symptoms worse. The prefrontal cortex, which helps regulate fear responses, becomes less effective when sleep-deprived, allowing the amygdala to become more reactive. Additionally, lack of sleep disrupts neurotransmitter balance, further exacerbating anxiety. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule, limiting screen time before bed, and practicing relaxation techniques can improve sleep quality and, in turn, reduce anxiety levels.

8. Is there a connection between gut health and anxiety?

Yes, emerging research highlights the gut-brain connection and its role in anxiety and the brain. The gut microbiome influences the production of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, which regulates mood. An imbalance in gut bacteria can lead to increased inflammation, which has been linked to anxiety and depression. Probiotic-rich foods, fiber, and fermented foods can help maintain a healthy gut environment and potentially reduce anxiety symptoms. While more research is needed, improving gut health through diet and probiotics is a promising avenue for managing anxiety naturally.

9. Can mindfulness and meditation rewire an anxiety brain vs. normal brain?

Mindfulness and meditation are powerful tools for reshaping an anxiety brain vs. normal brain. These practices strengthen the prefrontal cortex, allowing for better emotional regulation and reducing overactivity in the amygdala. Meditation also promotes the release of GABA and serotonin, neurotransmitters that help counteract excessive anxiety. Over time, individuals who engage in regular mindfulness practices develop greater resilience to stress and improved cognitive function. Even a few minutes of daily meditation can yield measurable improvements in anxiety symptoms and overall brain health.

10. What lifestyle changes can help balance anxiety and the brain?

Lifestyle modifications can play a crucial role in balancing anxiety and the brain. Regular physical exercise boosts endorphins and supports neuroplasticity, reducing anxiety symptoms. Exposure to sunlight enhances vitamin D production, which is linked to mood regulation. Limiting social media and digital consumption helps reduce overstimulation and information overload, which can contribute to anxious thoughts. Developing strong social connections and engaging in enjoyable activities can provide emotional support and promote a sense of well-being. Implementing these small but impactful lifestyle changes can help rewire the brain and foster long-term anxiety management.

Conclusion: Understanding and Managing Anxiety for a Healthier Brain

Anxiety is not merely an emotional state but a complex neurological condition that alters brain structure, function, and chemistry. The differences between an anxiety brain vs. a normal brain underscore the profound impact of chronic stress and fear on cognitive function. Understanding what causes anxiety in the brain allows for more effective treatment strategies that target its root causes. By addressing both the psychological and physiological components of anxiety, individuals can take proactive steps to rewire their brains, restore emotional balance, and regain control over their lives. Whether through therapy, lifestyle changes, or medication, managing anxiety is essential for maintaining long-term brain health and overall well-being.

brain function and anxiety, neurological effects of stress, chronic stress impact on the brain, fear response in the brain, overactive amygdala, neurotransmitters and mental health, serotonin and anxiety, cognitive effects of anxiety, stress-induced brain changes, brain plasticity and anxiety, mental health and neuroscience, emotional regulation and the brain, prefrontal cortex dysfunction, hippocampus and memory loss, anxiety disorder neuroscience, psychological stress and cognition, mindfulness for brain health, cognitive behavioral therapy benefits, neuroplasticity and mental wellness, stress resilience techniques

Further Reading:

The Neurobiology of Anxiety Disorders: Brain Imaging, Genetics, and Psychoneuroendocrinology

The Science of Anxiety (Infographic)

Disclaimer

The content provided by HealthXWire is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While we strive for accuracy, the information presented on this site may not reflect the most current research or medical guidelines. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. HealthXWire does not endorse, recommend, or guarantee the efficacy of any products, services, or treatments mentioned on this site. Users should not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of something they have read on HealthXWire. HealthXWire is not liable for any damages, loss, or injury arising from reliance on the information provided herein.